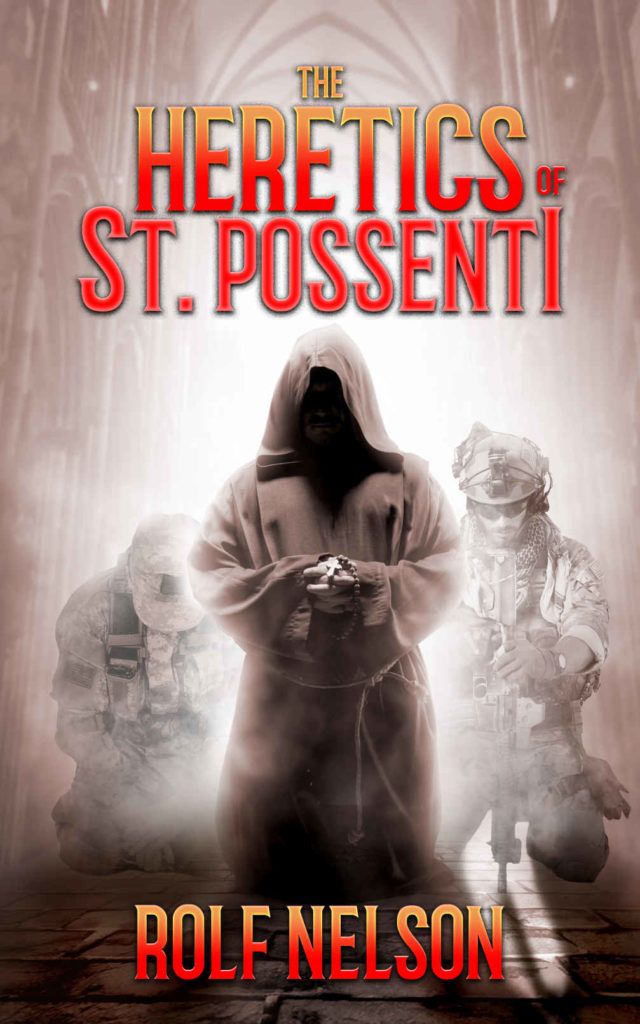

Heretic Monks

The status of Rolf Nelson’s bibliography is a bit confused right now. His first book, The Stars Came Back, was written in a screenplay format. The barest of action and setting descriptions, and a lot of dialogue, but engaging; Partway in you’re hooked and barely noticing the odd structure any more than you’d notice the style of english in Shakespeare.

His second book – Back From the Dead – isn’t really new, but instead the prose version of the first half of The Stars Came Back. I’m personally waiting to find out what happens after the first book.

A couple days ago, I was notified that a new book, The Heretics of St. Possenti, was available. Wonder of wonders, while it wasn’t a proper sequel to The Stars Came Back, it was a brand new story. A prequel of sorts. The story of how the mysterious order of combat monks in The Stars Came Back came to be.

In the past you’ve said that with The Stars Came Back you just had to write it. Like it was a story in your head that you just had to get out. Was Heretics the same way?

Not at all. It was more a small question, and a very small number of vocal proponents saying “this is A STORY!” that piqued my interest to the point where I was pondering: “Yes, how exactly DOES this happen?” I started gaming it out – what sort of person, what sort of events, how would they connect, how would the higher-ups feel about it, who would react badly, how would it support itself? Once you start to get an idea sketched out, I had to do research to see if it were plausible, or doable. Along the way I learned a lot about various aspects of the Church, and that altered the plot line more than a little bit. I still realize I know much less than I should about such a venerable institution

It’s a deeply philosophical book, one that looks at the supposedly pacifist nature of Christianity and finds that interpretation lacking, much as I’d previously written about how the golden rule was frequently misinterpreted to be “nice” instead of just.

It does start a bit slow, as a priest discovers how little he knows about what people need, starts hanging out in low places like Dojo’s and gun ranges, and decides the best way to help vets with PTSD and the church was to found a new order of monks – to give them purpose and to give the church strong men of faith.

A lot of philosophy and observations front loaded into the beginning will surprise no-one who’ve been paying attention to the manosphere in general, Jordan Peterson, or especially Vox Day. While I agree with much, even most of it, it came across a bit like a lecture and will likely shock those not used to the red pill. It segue’s from that to a more straight-out “how do we build a monastery and culture and deal with corrupt politicians” and “guys building stuff” story, then the beginnings of the impact it has on the greater world as the men it trains step back into it. The plot and narrative follow a more organic path than the classic build up to a major climax, so in some ways the developments had a less forced feel than a more traditionally plotted narrative would. You get to know a lot of the major characters, and get into their heads. While the early parts can as mentioned be a bit of an infodump, and toward the end, more in the way of related snapshots as the time scale expanded, it all held together and kept me up until two in the morning before I realized I had to put it down and go to sleep.

From the early part of the book, in a dojo learning self-defense:

When Thomas commented on the politeness, silence, and self-discipline among the younger members in attendance—quite at odds with what he normally saw in the community—the Shaolin monk responded wryly. “Lack of politeness and self-discipline is counterproductive. In here that fact is simply much more immediately apparent… and painful. Everyone benefits.”

An entire essay could likely be written on a nearly offhand, but critical mention that the choice to fight back against an attacker drastically reduces the intensity of related PTSD. There’s also a discussion of “living by the sword” in the biblical sense, that goes in a completely different direction than I’d have expected, and I’d already realized that it embodied the Christian version of Karma. The entire book utterly rejects the assumptions of post-modernism, implicitly and explicitly – and could not fulfill it’s job of telling the story of how men find purpose if it proceeded from a place where purpose was meaningless.

While there are a number of scenes and lines that, like a Ringo or Correia book, made me laugh or ponder them, my favorite has to the the following, utterly fitting to its scene:

Looking back on it later, it was not the best night, nor the worst. It was just the first.

While not the shortest read, it left me wanting to know what happened next, and maybe I should have opened with that.

Go buy it.