Over the last decade, I've run and played Pathfinder (I know...), played Dungeon World, and run ACKs and Classic (1st gen) Traveller. I've also had a fair bit of exposure to FATE, the recent version of Paranoia, and the world of darkness vampire setting. The less said about the latter, the better.

So what did Pathfinder get right? Mostly, a lavishly filled out game world and background, with solid art and production values, as the core system was "d20," a reskinned open-source D&D 3.5 which took off as Wizards of the Coast completely - in the opinion of it's fan base - messed up D&D with 4th edition.

What was wrong with it? I could go on, and have. In the end, the "crunch" of the various combinations of feats and abilities is annoying, but not lethal, especially to anyone who cut their teeth on Star Fleet Battles. It doesn't scare off a lot of other players.

It did make Lone Wolf Development a lot of money by selling Hero Lab.

Mostly it's about how the system inherently pushes players and the GM toward "if it's not explicitly allowed it's forbidden", and explicitly does so in "Society" play. How it limits the options of the characters, and pushes the GM, again, more explicitly in society play, to run adventures that are just tabletop versions of an on-rails first-person shooter, though perhaps with stats and complexity approaching a JRPG. In the end, it's boring. While characters can die, they are not expected to. The stakes are low, and the irritation over the failure points, like blowing a single allowed skill check roll for something that can and should be role-played, adds up. The game is also obsessively concerned with balance, and the complexity of the rules strongly encourages rules-munchkins trying to eke out every possible bit of damage or protection.

Of the time I spent playing Pathfinder, only a few moments jump out as memorable. Not because of the content of the adventure being run, but because of some bit of character improv on the part of the GM or a player.

I don't recall the original edition of Paranoia well enough to know how significantly the new version diverges, but it's still fun. Toy gun props are strongly encouraged. That said, I want to focus on three other games - two that set the stage for almost everything else that followed, and one that inherited most of the best. AD&D, Traveller, and ACKs.

AD&D - Not sure if I bought, or a friend bought, the AD&D books first, but I certainly was introduced to D&D in general via the basic set, with B1 / Keep on the borderlands. I was already familiar with wargames as a friend's dad had Afrika Corps by AH, among other games. Somewhere in a short span of years, not yet in high school, I got my hands on the core AD&D books, the Traveller Book - a consolidated version of the first few Little Black Books - and sundry other games I'm not covering today. I got to play both some D&D and Traveller in middle and high school, but other than an object lesson in why overplanning on the part of a GM is folly, as is counting on players to take the obvious road you laid out for them, I didn't appreciate what I had until much later.

ACKS only appeared in the last decade.

What makes them different?

First of all, Traveller is in space. That said, one of the offshoots capturing that classic Traveller feel is the Cepheus Engine, which has also been adapted to a fantasy setting called Swords of Cepheus. Where D&D/ACKs have you pick a class, Traveller allows you to opt for a career path. if you fail to qualify, you'll get drafted. The biggest kicker is that a character may very well not survive the creation process. Insofar as game mechanics, almost everything is centered on 2D6 rolls to hit or succeed. Unlike more strictly class-based games like D&D, you actually could acquire skills, and the mechanics included explicit ways to improve your basic stats - one of which was social rank. Finally, there were no "levels" - the skills and stats you had were it. Character time and money had to be spent to improve anything, including one's financial position, and the only real limit on what a character could go do was his wealth - what kind of passage or starship he could afford. Wounds are directly tallied off of your physical stats.

AD&D grew out of basic D&D. You can certainly see the skeleton underneath, but with more classes and their respective abilities, and a lot more charts for different possible actions or reesults. The DMG in particular has a lot more guidance on specific magic items, treasures, and resolving various obstacles. Where Traveller started out as three little black books, and Basic D&D was one slightly larger book, AD&D comprise three whole volumes - the monster manual, a player's handbook, and the Dungeon Master's Guide.

While numerous other systems grew up wildly diverging from D&D, it's still the 500-pound gorilla in the room, and it's legacy and assumptions can be seen everywhere.

ACKs grew out of the "Old School Revolution" - an attempt to go back to the basics, literally Basic D&D, and fashion a version that kept what worked, while making use of what had been learned since then about game design. Where a lot of RPG systems grew out of a desire to fix what was "wrong" about D&D/AD&D, the OSR, and ACKs in particular, assumed to greater or lesser degrees that the games were not broken.

To best describe ACKs, it has a simpler ruleset closer to D&D, but - especially with the player's companion - more flexibility in creating characters without going into point-buy systems like GURPS or Pathfinder (at least society play) or encouraging min/max designs. It also has a different assumed background, based more on a post/late Roman Empire than more traditional "medieval" tropes. Most importantly, Macris took the core assumptions are refactored a lot of the charts and concepts from AD&D back into the simpler and more cohesive rule set. Finally, it explicitly answered the question D&D never got around to - how to deal with higher level characters and their kingdoms.

What makes them the same?

First - they are both relatively rules and rulings-lite. AD&D sticks out as the worst offender with it's separate mechanics for doing different things - take unarmed combat for example - and yet, one can also fairly call most of the DMG as a catalog of exceptions to the basic rules. For that matter, once you get the hang of the basic fighter/cleric/magic user classes, most of the space on the more esoteric character classes, and all of the monsters, are to explain how the class or monsters ignore standard rules, or have other exceptions or special abilities. In short, splat. Nevertheless, the core assumptions that permeate the game give you a pretty solid idea of what was intended, so that when something comes up not explicitly handled, the GM can make a decision without having to apply a lot of thought or make up precedents out of whole cloth.

ACKs hones this to a fine edge. With a greater degree of rules coherency, and significant work by Macris to fill out tables and rules for economics and kingdoms, it scales better, and requires fewer rulings than AD&D while also having fewer rules and tables to look up.

Traveller, while skills-based, actually doesn't have characters acquire many skills. Characters are generally assumed to be able to do basic things like drive, access a computer terminal, play a round of poker, and so on. Having a skill at even level 1 is the equivalent of a journeyman - the character can make a living as a professional in that field.

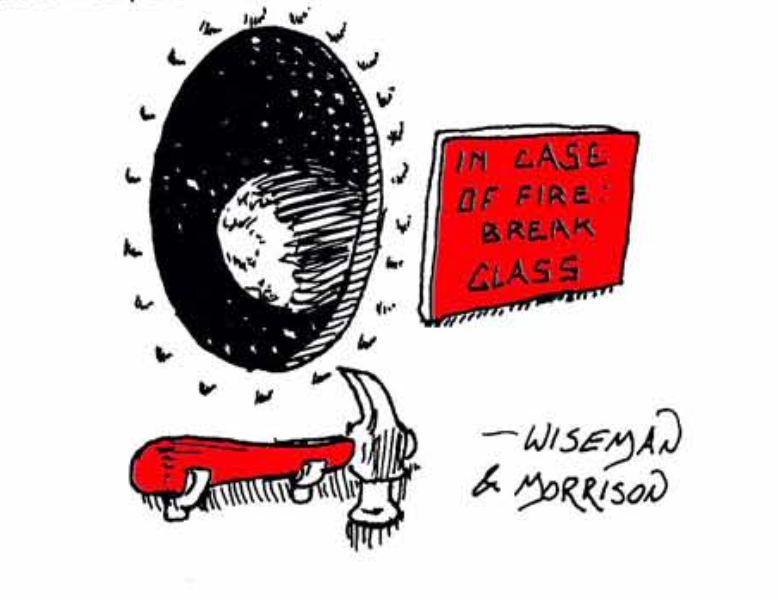

Second - they inherently encourage actual role-play. As one friend put it - avoid rolling dice if you possibly can. The GM/DM might roll dice to look things up on a table, check for reaction or morale rolls, and such, but where games like D&D3x and pathfinder will have you make explicit "perception checks" and "knowledge" rolls - and if you don't have the requisite skill, you're toast - these games work best when the players actually develop plans in response to what's in front of them, and the GM decides what would reasonably happen as a result. The dice are there to introduce randomness when no clear path exists, or to allow for the unexpected.

Coming up with a reason why a band of orcs are happy to see the party opens up a lot of possibilities beyond the boring and predictable "oh, we kill them."

Third - they have liminality. Everything hangs on the decisions being made by both the GMs and the players. The GM may be the final arbiter of how the rules are applied in the context of the campaign, but unless he is the worst sort of GM running an adventure on rails, the players are free to completely change the state of the game world through luck and clever planning - even the best GM's have experienced players going after a red herring and ignoring the obvious hints thrown in their path. The GM then figures out what happens next - and the players respond to that. It's not all reactive. The GM can figure out what verious factions are up to, helping to guide decisions of who reacts how, and the players can very much plot how theey're going to set up to take on a crypt or tower. Or not.

Neither side creates the game world, or chages its state, alone. It is always in flux.

Fourth - they are not balanced. Players can always, very quickly, get in over their heads. Traveller is the most extreme example of this with character death in generation. ACKs is perhaps the most "balanced" of these, and even it is nowhere near the current D&D5/Pathfinder standard of making sure every class is able to deal out combat damage, or buff, or otherwise be "just as important" as if it was a slowed-down version of World of Warcraft.

Fifth - the campaign is the thing. The characters may die, but the party lives on. This is of course true to some extent with all RPGs if players are but wise enough to see it, but it's particularly twisted into grotesquerie with Pathfinder's "society play" which on the one hand has a massive meta-campaign, yet the on-rails "adventures" are designed for arbitrary players to drop in, and people to play at any venue instead of at a cohesive table driven by one GM. The shared world of the player characters is so amorphous as to be useless.

ACKs, Traveller, and AD&D instead encourage a style of play where you may have modules, but they are part of a larger world that the players explore, affect, and find their own adventures as well. An almost sitcom-like "here's our base, whoever shows up that day goes on expedition" style of play works outstandingly well - though less so in Traveller without some handwaving about how "we told our friends that we were going to ..." Exploring the wilderness is explicitly part of both ACKs and AD&D play. Even in the Dwimmermount campaign I run, the players have spent significant time developing a barge trade, ransacking several lost sites hinted at in the main megadungeon, and exploring and encountering weirdness in the wilderness. For that matter, implied in AD&D and more strongly in ACKs, you want to be in the wilderness exploring and not at the heart of civilization, because as you get to a level where you acquire lands and followers, the city rulers may not be too happy with you setting up shop in their demesne.

So. Modules. For our purposes, an "adventure" is something with an integral storyline that th echaracters are expected to follow, perhaps with several branches. It's on rails, the end result is mostly ordained. A module is a splat book with maps, some factions and personalities, and several hooks to point the players at those. In the best, the wilderness is at most vaguely described beyond a day's march, and they can be dropped in anywhere. Alternatively, there is a decent regional map, but most of it is effectively unexplored wilderness. An example in Basic D&D is B1, Keep on the Borderlands. In ACKs, you have Sakkara - an homage to B1 - and Dwimmermount. More recently, Secrets of the Nethercity bills itself as an adventure, but also claims to be designed to drop into any campaign.

Are they good or bad? Some, like Jeffro, have observed that campaigns in practice tend to devolve into characters going after whatever they find shiney that day, and not focusing on one "dungeon" over and over again. There is truth to that - any players worth their salt will start striking out to see what else there is beyond a single dungeon, and random rolls and treasures, plus a bit of GM inspiration, can lead to most of a campaign doing its own thing. My own experience with Sakkara and Dwimmermount has been a blend - a lot of time exploring outside of the dungeon proper, but a lot of time focussed on the dungeon per se.

It helps when things discovered as a result of random - or not so random - treasure rolls are helpful for tackling issues in the original dungeon. Some of those things can both be immensely useful, and cause massive logistical nightmares for the players.

My advice? Modules can be an excellent place to start - with caveats. First - as much fun as Dwimmermount has been, in the future I'd lean towards something smaller like Sakkara, fleshed out just enough to give you a starting point to riff off of. If you design your own world and dungeon locations, stick to smaller ones with a large wilderness map, and civilization somewhere nearby. For individual "dungeons", several floors at most, and the more floors, the smaller the map footprint per level - towers aren't typically hundreds of feet per level. Locations substantial enough to demand multiple shots to find out "what was past that last room" are a good thing, but spending days drawing out page after page of maps likely will not yeild the results you want with players worth their salt.

In short, give yourself and your players a chance to set and create the world as you play.